Water – Too much / Too little

Writing at the end of April, I am wrapped up well and summer seems a long way off. But it is at this time of year that water companies and farmers look anxiously at the levels in their reservoirs as well as river flows and groundwater levels. If we have another scorcher in 2023, will we avoid water rationing, grow enough potatoes and will our wildlife prosper?

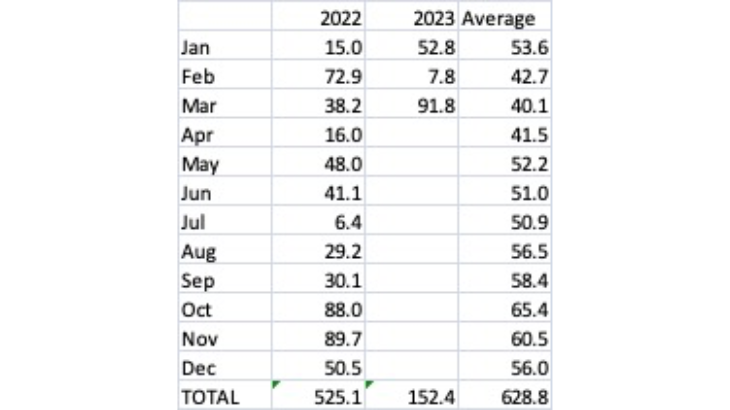

At the end of March, Anglian Water, Thames Water and Severn Trent were all reporting well filled reservoirs in our area. Pitsford School has a Met Office weather station on the roof and supplies national data. If you don’t have your own weather station or rain gauge in the garden, the website is a good place for finding local data. The format takes a bit of getting used to, but it’s all there. (http://www.northantsweather.org/) In the following table you can see that October and November 2022, and March 2023, were all above average.

I well remember the drought year, 1976. Late summer 1975 was hot and dry, and the reservoirs never filled in the winter 1975/6. Our brook dribbled to nothing and without irrigation there was a massive crop of tiny apples costing a lot to pick and making me no money.

Even if we are starting the summer of 2023 with full reservoirs, we should not squander water. I spent many years irrigating my own crops and then working as an irrigation consultant. We took electronic measurements of soil moisture every 10 minutes in farm crops, orchards and greenhouses. Our probes had sensors every 10cm down to 50cm or sometimes to 1m. Here are some observations I made.

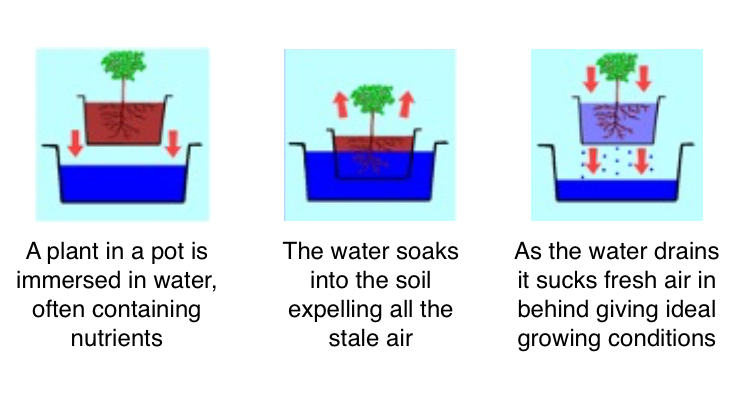

1. Soil is roughly 1/3 particle, 1/3 air and 1/3 water when full. ‘Full’ means that for any water added to the top surface, an equal amount will flow out to drainage. If the drain is blocked, a full soil can become saturated or ‘water-logged’: the water has driven out the air and the roots cannot breathe. Conversely, water draining through a soil dissolves nutrients for the roots, cleanses unwanted elements and draws in fresh air with oxygen from the surface. Therefore, a good rain or irrigation should fill the soil down to the maximum rooting depth of the crop, say 50 – 100 cm. Watering little and often is not good: the plants develop surface roots only: nutrients deeper in the profile are not mobilised. The leaves turn yellow.

2. Rain or watering will fill the top layer of soil first and then gradually fill the middle and lower layers. A thunderstorm may overfill the top layer and water will run away over the surface without penetrating to depth. I remember two crops next to each other, potatoes in one field and onions in the other. The potatoes were grown on ridges, the onions on the flat. We had probes in both. There was a thunderstorm on Saturday when 15mm rain fell in 30 minutes. The probe in the onions measured exactly 15mm increase in soil moisture; the probe in the potato ridge measured nothing. The rain had run off the ridge into the furrow away from the potato roots. On the Sunday, it drizzled all day and a further 15mm fell. This time, because it fell slowly, both probes recorded the full 15mm.

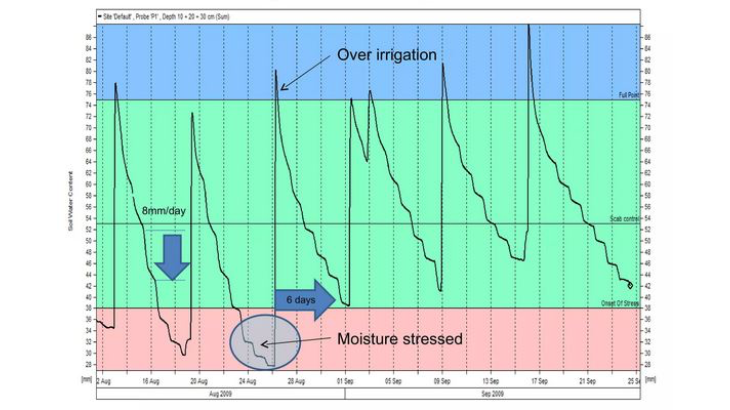

3. Because water use is driven by photosynthesis, plants use water in the daytime but not at night. Graphs of soil water show a stepping effect so it is easy to see where the roots are working and how much they are using each day.

Graph 1 above shows sensors in potatoes at 10, 20 and 30 cm summed together. It is easy to see the steps when the plants are growing well and when they start to run out of water.

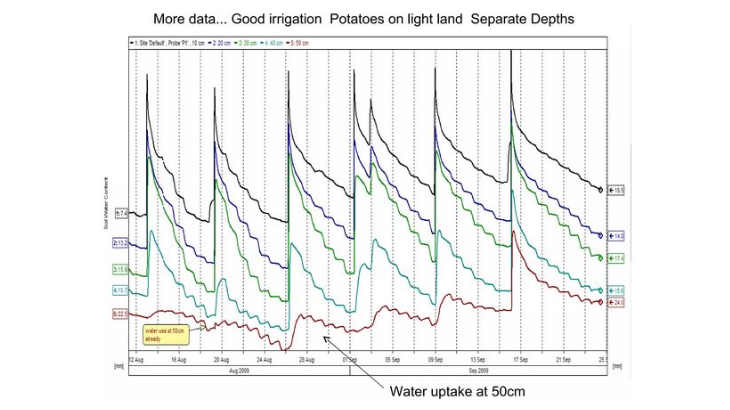

Graph 2 shows five sensors on a probe (10cm to 50cm) graphed separately with the shallowest on top. It shows water flowing through the profile at each irrigation but not reaching 50cm till 16th September, when the soil moisture content shown by the deepest probe rises sharply. At this point the deep roots become really active.

4. Using a device to measure sap-flow in a tree trunk, one can see the same effect. So much so that during a total eclipse of the sun, an oak tree stopped using water. But the tree was large: the message took time to reach the roots. Water use stopped 15 minutes after the beginning of the full eclipse and did not start again until the eclipse was well finished!

5. Gardeners are often told to water in the early morning or late evening. It may be important not to scorch the leaves of tender plants in full sun, but it makes little difference to the water reaching the plants’ roots. Droplets left on the leaves will evaporate when the sun shines or the wind blows.

6. How often should we water? That depends on the proportion of sand / silt / clay particles in the soil and the amount of organic matter, humus and other constituents binding them into ‘aggregates’. The large particles in sand have less surface area to hold water by capillary attraction. The opposite is true for heavier silts and clays. But water capacity of all soils is improved by some organic matter.

In graph 1 (a light soil) you can just see that the top 30cm of soil is full at about 75mm of water and getting dry ‘stress’ at about 38mm. This means that if a plant’s roots are 30cm deep, you subtract stress from full and find that they have 37mm of water available. At maximum, you can see that the plants are using up to 8mm per day and therefore irrigation of 35 to 40mm is needed every 5 – 6 days. That’s a lot of water!

In our gardens we are not usually trying to win the potato prize at the county show! Nevertheless, if your soil is light it will need a good drenching every week. In a heavier soil, plants tend to use the same amount of water per day but need watering with more water less frequently.

7. Plants in pots have far less soil to explore and less water is available, especially as we are now using peat-free compost with poor water-holding capacity. In hot weather, outdoor pot plants need watering at least every other day with feed once per week. Make sure water drains through and out of the bottom every time you water.

However, indoor plants need far less water. There is less light driving photosynthesis and less air flow causing evapotranspiration. In the summer, I dunk and drain plant pots in the sink once per week, but in winter I leave them 2 – 3 weeks at a time. Growing strawberries in bags in a greenhouse, with the dripper removed there was no sign of stress for 14 days.

8. If you have drip irrigation, treat it like growing in a pot. The wet area under a dripper is onion shaped but the wetted area seldom spreads more than 25cm. Therefore drippers should be a maximum 50cm apart. Remember with drip, roots accumulate under the dripper. Therefore after rain falls overall, the roots are only active under the dripper and water will run out there much quicker than in the surrounding soil.

I find soil and water very interesting. But until I saw those two graphs above, I never thought carefully about what happens under ground.

One final point: in 2022 many newly planted trees were lost in the hot, dry summer. This was unnecessary. I have planted thousands of fruit trees, including in 1976, and I have never lost one.

🔹 If possible, plant bare root trees in November when the leaves are off but while the soil is still warm enough for immediate root growth.

🔹 Water thoroughly after planting.

🔹 Protect from rabbits.

🔹 Remove competition from grass and weeds and keep bare soil one meter round the tree for at least one year. (Grass takes a lot of water. If using a herbicide is unacceptable, weed by hand and/or use a mulch).

🔹 Any mulch, such as cardboard, will prevent weed growth but it must let water through. Straw will intercept light summer showers and the water will evaporate before reaching the soil. With straw, it will be necessary to water thoroughly at least once per month.

Keep planting and growing! It is good for the planet. If you have any water related issues, give me a call.