Understanding the Biodiversity Crisis

It is increasingly recognised that biodiversity loss or the loss of Nature is as existential a threat as the climate crisis. The relationship between Climate and Nature and the importance of the global biosphere in mitigating climate change impacts was first acknowledged at the Conference of the Parties (COP) 26 in Glasgow in 2021. In the following year, in Montreal, the COP for Nature declared a Global Biodiversity Framework within which was described a global vision of our world living in harmony with nature by 20501. To achieve this vision the agreed target for all nations was the restoration of biodiversity by 30% everywhere by 2030 and to submit practical plans to achieve that at COP 16 in 2024.

On 21st October 2024 COP 16 for Biodiversity or Nature began in Cali, Columbia. The environment minister for the Columbian government, Susana Muhamad, stated in preparation for this COP:

“There is a double movement humanity must make. The first one is to decarbonise and have a just energy transition,”

“The other side of the coin is to restore nature and allow nature to take again its power over planet Earth so that we can really stabilise the climate.”2

Why is there such focus on Biodiversity (Nature) restoration?

The issue is explored in this short film (Why is biodiversity important)3.

There are many YouTube clips with David Attenborough discussing this question for different audiences. I selected this one because the narration is direct and the animation beautiful. It is worth mentioning that such ‘remote’ viewing is not entertainment and the message is stark.

Since the industrial revolution in the 18th Century and particularly since the 1970s a combination of fossil fuel extraction and burning, deforestation, intensification of agriculture especially livestock farming, urbanisation, and pollution, have collectively pushed up global average temperatures to 1.2 degrees higher than pre-industrial levels and caused a 69% decline in species across the world. We know that it is the exploitation and extraction of resources that has been the cause of species decline but the impacts of climate change caused by global heating add to the vulnerability of Nature. CO2 in the atmosphere continues to increase as a result of human activity, causing extreme weather, wildfires, flood, drought, food insecurity and economic uncertainty.

Consider these Nature stats

The Biodiversity Intactness Index developed by Natural History Museum scientists is a measure of how much of an ecosystem’s natural biodiversity still remains despite human impacts.4

A healthy global biosphere should have a Biodiversity Intactness Index (BII) of 90%. The average global BII is 77% although there are wide variations. The UK is among the most biodiversity-depleted countries in the world with a Biodiversity Intactness Index of 42% - the lowest in the G7, while Canada achieves more than 90%.

In 2015 the weight of wild animals made up just 4% of the global mammal biomass. The remaining 96% came from humans and livestock, while 70% of all birds are poultry.5

Only 1.2 million of 7-8 million species thought to exist have been described and catalogued. We know that extinction is occurring faster than natural rates of extinction and some species will become extinct before they can be found and with that the potential for new foods and medicines.6

The biomass percentages of humans, livestock and poultry in comparison to wildlife are serious indicators of the amount of natural vegetation cleared for intensive food production methods, resulting in habitat loss for millions of species.

How can we connect with the problems facing nature?

The starting point has to be a consideration of our planet – its oceans, continents and islands; the ice fields, fresh and salt water, soils and minerals; the great air and water currents that circulate heat, moisture and nutrients around the planet, its position in space and the protective layers it provides to enable all life to exist.

BUT it is the biosphere – the variety of life that creates the whole – the living and breathing earth as David Attenborough describes it. The biosphere is the living planet – life on earth.

We know that biodiversity is the variety of life, from genes to bacteria to the millions of unseen soil microbes; from fungi to plants and animals, including us.

Life exists at various scales from the biomes of tropical and temperate forests, mountains, grasslands, deserts and the oceans to the communities in a single forest, a tree or a log. Life exists from under the earth’s crust to high above the atmosphere. There is evidence that microorganisms are involved in the creation of the silts that lubricate the movements of the great tectonic plates that form the earth’s crust.7

Biodiversity provides the mechanisms of planetary processes but from a human perspective it also provides food, medicine, energy, textiles. Over half of global GDP is moderately or highly dependent on nature8.

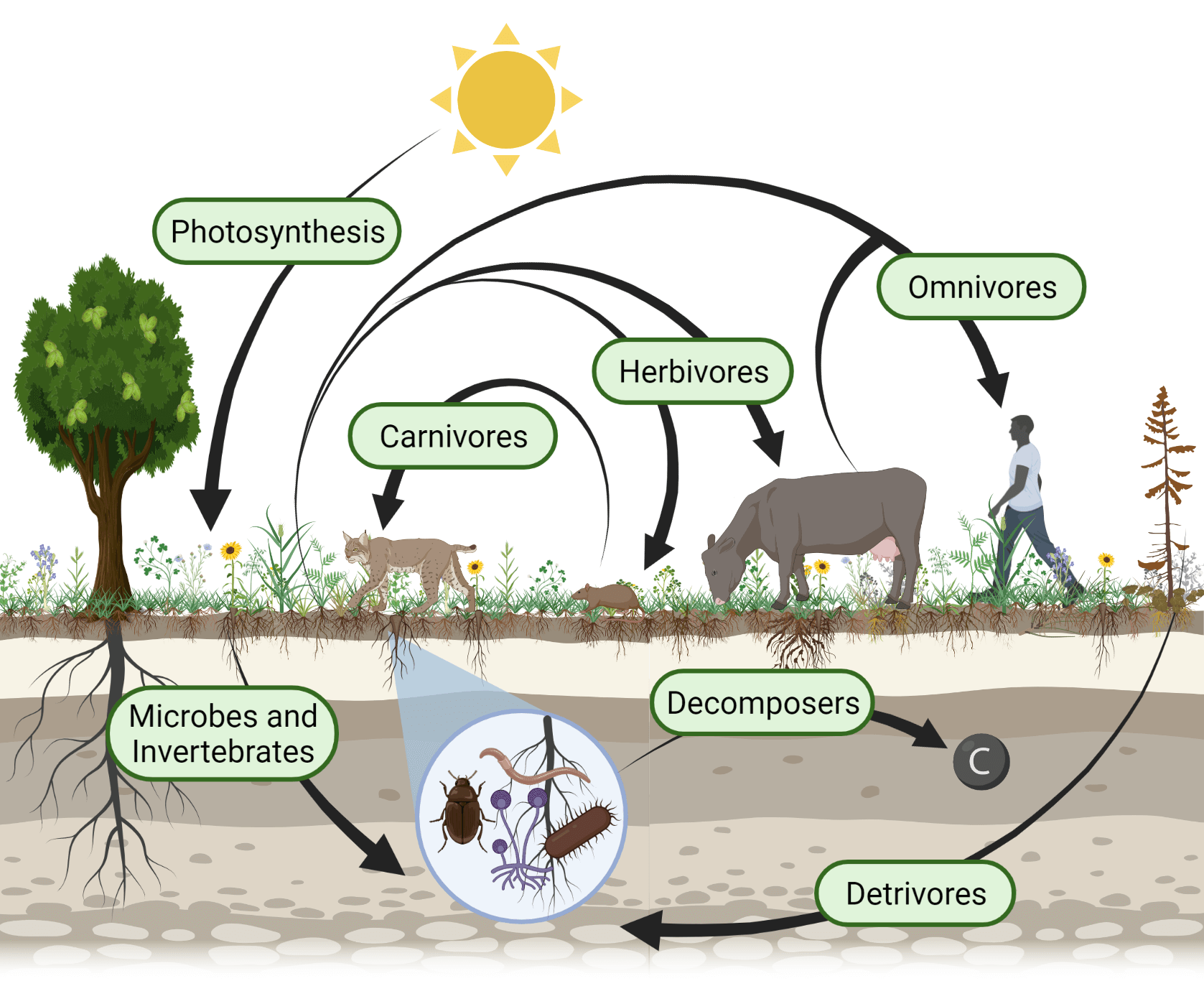

Following from the importance of the global biosphere we could remind ourselves of school biology and consider the following diagram.

Image credit: https://www.noble.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/energy-flow-infographic.png

Whether we consider the planet as a complete ecosystem, or a forest, an individual tree or the inhabitants of a log, all ecosystems operate in the same way: inputs are processed producing outputs which either feed back into the system, are emitted to the air, water and soil, or transported out of the system. These are natural processes essential in maintaining any ecosystem structure and are in equilibrium with each other.

Ecosystems are not static: they are not discrete entities that are closed off – even a remote tropical island will have huge variations in the ecological systems it supports via ocean and air currents. Colonisation of derelict land by plants will connect beyond that derelict land.

But all ecosystems operate with the same ingredients the planet provides: the light and heat from the sun, rainfall, air movements, mineral cycling, transpiration, respiration, photosynthesis, death, decomposition and recycling.

The circular economy of each ecosystem even as one merges with another is sustainable because as a system it has evolved its own checks and balances to achieve equilibrium.

A pristine ecosystem with no interference is 100%. At an intactness index of 90% an ecosystem remains healthy and has inbuilt resilience to regenerate to 100% e.g. after a flood or invasion of a foreign species such as locusts. Once an ecosystem declines below 90% its resilience is compromised.

Ecosystems are an expression of how the planet as a whole works – the interconnections of structures and processes that operate at all levels. Understanding that is essential.

If any part changes, the system will change for better or worse and if the latter the planet will tip into instability. If the polar ice melts the whole of the planet and of life is affected. Ice melt is at tipping point. The Amazon Rainforest, one of the most diverse ecosystems on our planet, is at tipping point because of deforestation. The balance between the moisture received through intense tropical rain and the layered density of vegetation from the tallest at beyond 30 metres to the moss at soil level is changing. The moisture exchange between the atmosphere and the vegetation is critical to sustain the forest. As trees are cleared the moisture exchange declines to a point where the rainfall is decreasing and the soil is drying out; as a result primary forest cannot be supported. A secondary forest takes its place which is much less diverse for plants and animals, and the ecosystem changes. Climate change continues to exacerbate the problem as it causes shifts in global circulation and warmer air with an increased capacity to hold water vapour rather than releasing it as rainfall. Therefore when rain does fall, the intensity and volume can be catastrophic.

Such examples illustrate the interconnectedness of the problems biodiversity faces but also that those problems face us all.

The Global Framework for Biodiversity acknowledges the paramount importance of biodiversity restoration for the integrity, health and sustainability of our planetary systems and COP 16 aims to commit national plans to action. The target of 30% increase in land managed for Nature by 2030 is being translated into Local Nature Recovery Strategies.9

Emphasis is on the locality and a consideration of what exists where, and how any habitat can be managed, improved and expanded to full intactness.

Any Local Nature Recovery Strategy follows the ‘Living Landscape Approach’ set out by the Wildlife Trust, which aims to use wildlife corridors that connect smaller sites together with larger ones. Wildlife needs natural networks – this enables movement of animals, seed dispersal, pollination and the effective operation of nutrient and water cycling.

In the past, conservation has focussed on specific sites such as the National Parks but between such areas, biodiversity has been decimated through urbanisation – hence the UK’s 42% BII.

Understanding our ecosystems, the environmental factors such as soil type, local weather, exposure, and drainage is vital and expert assistance may be required. However, a starting point for community leaders and interested volunteers could be to note what habitat potential exists and build on it – the roadside verges, hedgerows, field margins, streams, marshes, rivers, coppices, woodland, the tree canopy, the soils. Even traffic islands have potential, and private gardens are very important. We can then begin to see how the local ecosystems may connect with those further afield. How close are we to a larger area of woodland such as Harlestone Firs or Salcey Forest and do any streams or wetlands connect to the Nene River valley system?

BUT we need to have a vision of the environment we want to live in or bring our children up in to.

Can we envisage our towns, villages and countryside where Nature is dominant and ensure that everyone wherever they live has access to good quality green space?

To conclude:

We must acknowledge that Nature and the Climate are existential threats and the cause lies with all of us.

Therefore we all have a part to play in biodiversity restoration and carbon reduction.

We need to think of ourselves as part of Nature and not a controller of it.

Could we consider that we are of no more importance than the humble worm which aerates the soil or the bumble bee which pollinates our apple blossom?

Nature will provide the solutions if we allow it.

‘Peace with Nature', is the message sent from COP 16 in Colombia to the world. The United Nations’ Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, explains that

“making peace with nature requires understanding that we are facing a triple crisis that intertwines climate change, pollution and loss of biodiversity, which, in the end, becomes a suicidal war because without nature, humanity could not exist on the planet.”10

References

1. https://www.cbd.int/gbf/vision

2. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/aug/22/nature-catastrophe-biodiversity-summit-president-carbon-emissions-climate-breakdown-susana-muhamad-aoe

3. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GlWNuzrqe7U

4. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/services/data/biodiversity-intactness-index.html

5. https://ourworldindata.org/wild-mammals-birds-biomass

6. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/11/extinction-facts-wildlife-attenborough/

7. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336502382_Plate_tectonics_drive_deep_biosphere_microbial_community_composition

8. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/esg/nature-and-biodiversity/managing-nature-risks-from-understanding-to-action.html

9. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-nature-recovery-strategies/local-nature-recovery-strategies

10. https://www.cbd.int/conferences/2024