The Problem with Methane (CH4)

Addressing methane is important because it accounts for about one third of all the greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change.

In more detail, methane is a powerful greenhouse gas with over 80 times the 20-year warming power of carbon dioxide. However, in the atmosphere it breaks down to carbon dioxide and water. Its half-life is about 12 years. To arrive at a CO2 equivalent, methane is often given with the figure 20 or 100 in brackets to show whether it is based on a 20 year or 100 year comparison with CO2.

Alice Rocha, M.S. from University of California in Davis, employs this analogy in her blog:

“Imagine you have two bathtubs. Both have faucets that are on, and water is flowing. However, only one of these bathtubs has a drain. The tub with the drain represents methane and the one without represents CO2. Because the drain is removing water, the tub will not fill up and overflow. That is what happens with methane in the atmosphere. Its short-lived nature means that the gas is actively being removed from the atmosphere and thereby reduces its contribution to warming over long periods of time.”

It is important to keep this in mind when putting a numerical figure on methane, but the fact remains that today, the faucet (tap) is bigger than the drain!

Methane is responsible for at least 30% of today’s warming. During 2019, about 60% (360 million tons) of methane released globally was from human activities, while natural sources contributed about 40% (230 million tons). The sources due to human activity are fossil fuel operations (33%), animal agriculture (30%), plant agriculture – biomass, rice etc (18%), landfills (15%) (source: Wikipedia).

Detecting Methane leaks

In April 2024 MethaneSAT was launched aboard SpaceX's Transporter 10. It is a satellite programme that monitors methane emissions around the world with very high resolution cameras. Its data will be available on-line for free. MethaneSAT is an American-New Zealand space mission.

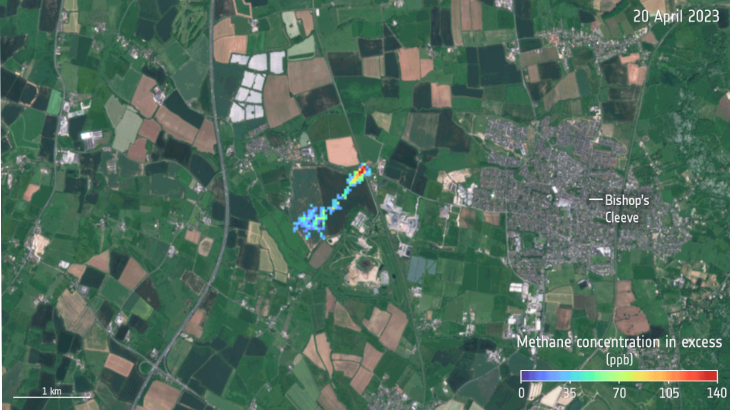

In December 2024, photos showing a methane leak in Cheltenham were released. These came from the earlier GHGSat satellite data – part of the European Space Agency’s Third Party Mission Programme. This is the first time methane emissions in the UK have been detected and rectified. You can read more on https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/UK_methane_leak_spotted_using_satellites2

Russia is responsible for the greatest quantity of leaked methane, but small wells (‘nodding donkeys’) in the US Permian Basin (Texas and New Mexico) are also to blame. Many are privately owned, some are flared, some not, but the owners are only interested in black gold and have no way of collecting and selling gas.

It will be interesting to see what satellite initiatives reveal in future.

Natural Methane Emissions

Much is made of natural methane emissions, but these are fairly constant and as long as they remain so, the natural breakdown of methane keeps a healthy balance. What does not seem to be certain is the extent to which global warming will form a loop to increase natural emissions emanating from melting ice-caps and permafrost.

Anaerobic Respiration in Land-Fill

We have heard a lot recently about residents not using their food-waste bins. The Council makes money for us out of biogas from our food waste. But more important, by chucking food waste into the general waste it ends up in land-fill where air is largely excluded. Anaerobic microbes get to work and turn it into methane. Not a good idea! If you see anyone putting waste food into the general waste bin, you need to say something.

Enteric Fermentation in Ruminants

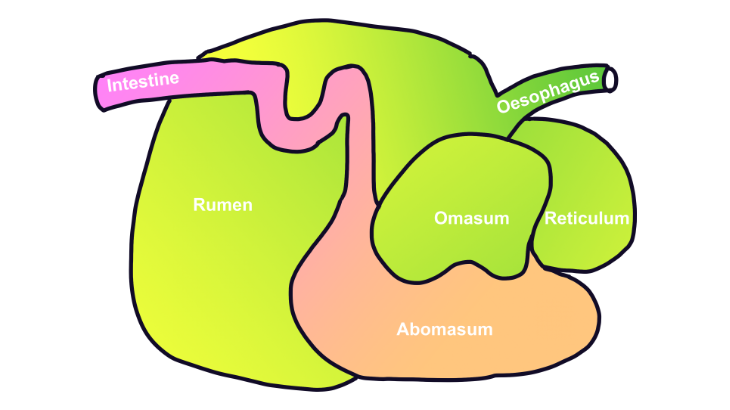

Methane is produced by ruminants belching (with a small amount of flatulence added). Ruminants include cattle, bison, buffaloes, sheep, goats, antelopes, deer, giraffes, and their relatives. They have a unique digestive system that allows them to use energy from fibrous plant material. Unlike monogastrics such as swine and poultry, ruminants have a digestive system with four chambers in the stomach designed to ferment feedstuffs and provide precursors for energy for the animal to use.

Cattle typically spend more than one-third of their time grazing, one-third of their time ruminating (cud chewing), and slightly less than one-third of their time idling where they are, neither grazing nor ruminating. A cow can produce 150 L or more of saliva daily! This saliva controls the pH and allows microbes to thrive breaking down tough fibres and releasing lots of gas. Carbon dioxide and methane are produced during the fermentation of carbohydrates. They are either removed through the rumen wall or lost by belching. Methane cannot be used by the cow’s body systems as a source of energy.

For anyone interested in the detailed digestive system of ruminants, there is a good description at http://extension.msstate.edu/publications/understanding-the-ruminant-animal-digestive-system.

Reducing Methane from Cattle

Some people have decided to become vegetarian or vegan as the only way to solve the methane problem, but I don’t think the majority of the public will accept that, nor do I think it is necessary. Also artificial meat is a long way from becoming affordable and main-stream. Without cows and sheep, our traditional English landscape would disappear. Most of the hedges would vanish together with the habitats they provide for wildlife.

We cannot eat grass, but our maritime climate and rolling hills produce very good grass. We have enough golf-courses and pony paddocks. Some land could and should produce more timber, but much of that land is not suitable for crops such as cereal, pulses, vegetables, fruit, oilseeds and sugar. Cows and sheep prosper; and we, as omnivores, with meat and milk in our diets, prosper too. How can we keep methane levels at reasonable levels?

The way we grow beef cattle in the UK is very different from the US. In America, cattle are normally finished in ‘feed lots’ where the feed is brought to the animals. American farmers claim that because cattle reach the required weight in less time (18 months), their methane output is less per kilo of meat. However, most British consumers would not be happy if our farmers were to adopt a similar system. The peak slaughter age for UK beef cattle is around 22 months.

Dairy cows live longer: The natural lifespan of a dairy cow has been reported to be approximately 20 years; however, research has highlighted that it is more like 3.6 lactations (approximately 6 years) in the UK and 2.8 lactations (approximately 5 years) in the USA. (https://a-z-animals.com/blog/cow-lifespan-how-long-do-cows-live/)

Below is a diagram of how we feed our livestock in the UK taken from the recent National Preparedness Report but originating from the WWF. (Cottee J, McCormack C, Hearne E, Sheane R. The future of feed: How low opportunity cost livestock feed could support a more regenerative UK food system: WWF-UK, 2020)

Apart from the age of slaughter, are there other ways of reducing the methane output of cows and sheep? There is no single solution to cutting emissions, but rather a toolbox of strategies.

Healthy livestock are more productive and efficient, meaning that fewer emissions are produced per unit of food output.

One of the most widely discussed solutions to methane emissions is the use of feed additives such as Bovaer, which has been shown to reduce methane production by up to 30%. These feed additives do need to be fed very regularly - twice per day, and there is a cost associated with them.

A Northern Irish farmer, John Gilliland, Professor of Practice at Queen’s University Belfast, has been researching the use of coppiced willow in cattle grazing, and the effect this has had on reductions in methane. He visited Australia to look at work of feeding red seaweed, asparagopsis, to cattle to reduce methane emissions. “What interested me even more was a trial in the neighbouring paddock. Now you have to remember the definition of an Australian paddock. A paddock in Irish terms is about 1 hectare in size. A paddock in Australian times is 100 hectares. In this 100-hectare paddock was a silvopasture of grazing trees which the cattle were allowed to graze.” So Professor Gilliland who already had 30 years of knowledge of willow production, set up a trial. You can read the rest of the story on his blog for the Low Carbon Agriculture Show: https://www.lowcarbonagricultureshow.co.uk/exhibitor-blog-2025/coppice-willow-cattle-grazing-way-forward-methane-reduction

Willow leaves contain high quantities of tannin which disrupts the production of methane in the rumen. This was a pilot project and we must wait to see if results can be replicated.

Conclusion

There is no one magic bullet to reduce methane in the atmosphere. Its effect on climate change cannot be denied.

Reducing leaks from oil and gas production and distribution is number one. Secondly, we have to reduce methane emissions from agriculture, in particular from ruminants. As there are more people on earth and they mostly want to eat meat, we each have to eat less meat. I have not mentioned milk and cheese: it may be easier to reduce methane from dairy cattle, especially if they live under cover. Particular attention will be needed to handling of manure and slurry. But there are exciting developments in farming to reduce the output of ruminant methane. Many farmers are harvesting their methane to provide electricity. We will never eliminate methane, but we can reduce it; and personally I shall continue a modest diet including some meat, milk and cheese!