Offsetting and Carbon Trading

I am very suspicious of offsetting. An old friend was persuaded by her heating oil supplier to give money to forestry in India. She has travelled to India many times and has a soft spot for the country and its peoples, so she was easily persuaded. In theory, the trees would mop up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere equivalent to that emitted by her oil-fired boiler. But how to know? How many trees? Over what period? Who will care for them and measure their growth? Is this ‘greenwashing’ or can she rest with a clear conscience that she is not harming the planet by burning oil? Would it not be better to stop burning oil AND to plant trees in India?

Early in February, I spent a day at ‘The Low Carbon Agriculture Show’ at Stoneleigh, the site of the old Royal Agricultural Show. It was busy with farmers travelling from afar. There were two days of talks, but I did not attend these, preferring to ask focused questions at the many stands. There were over 120 companies representing renewable energy; low carbon transport & machinery sectors; together with suppliers of innovative technology and advisors on carbon and environmental land management. Electric Land Rovers and sophisticated drones caught my eye, but I was more intrigued by the large number of companies involved in Carbon and Biodiversity offsetting.

A key element in carbon offsetting is to be able to measure carbon change in an area of land. Various carbon calculators are on offer including Agrecalc, a carbon footprint tool developed by Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) and its consulting division, SAC Consulting. These calculators are not all the same and it will take time for a standard to evolve.

For forestry it is relatively straightforward to estimate the amount of carbon stored in the trunks of trees; it is more difficult to estimate what goes on under the surface in the soil but a system has been agreed.

For crop land, carbon is stored below ground as decomposing roots and other organic matter incorporated by worms, and the farmer must show the initial carbon content and an increase over the years in order to offer an offset. For calculators like Agrecalc to work, good data are needed. The situation is dynamic: organic matter is constantly added and broken down. Traditionally a farmer takes soil samples at two depths with an auger following a W pattern across the field (see photo of me doing this in China). The samples are mixed to provide one composite (average) sample. A laboratory sends back an analysis of N (nitrogen), P (phosphorus), K (potassium) and Mg (magnesium) to help the farmer apply the right amount of fertiliser plus an estimate of organic matter. With carbon trading and offsetting, a lot of money is involved. More sophisticated and detailed soil carbon analysis is required to measure changes over time across the land and at depths down to one metre or more, using mobile sampling machines.

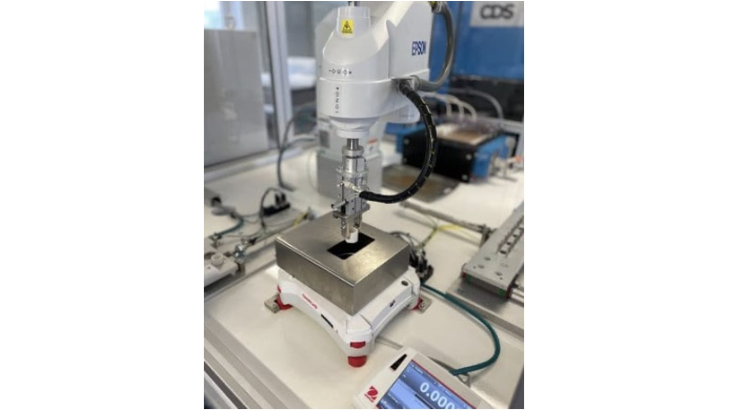

Back in the laboratory the analysis of soil samples can be an automated process that lowers the costs of processing them.

Farmers are losing the Basic Payment Scheme, a grant based on the area of land farmed. The alternative is to engage in one of the government’s Environmental Land Management Schemes (ELMS). Government schemes are outlined by DEFRA in a small leaflet called ‘New Farming Policies and Payments in England’ and there are more details at www.gov.uk/guidance/funding-for-farmers. There are separate schemes for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

But to many famers these are complicated and bureaucratic, and commercial carbon offsetting might seem more attractive and simple. At the show there were numerous brokers and consultants offering to help farmers connect with those seeking offsets. For example, I picked up a brochure from a Cambridge company called Insenti. Insenti's software platform connects farmers who are looking for investment in regenerative agriculture or green energy projects with their downstream customers, who are looking to reduce ‘Scope 3’ emissions in their own supply chains. This is known as insetting. However, none of the consultants offered a clear way in which a famer could measure changes in carbon and sell this directly to food manufacturers and suppliers, or other industries such as airlines.

The situation is much clearer in biodiversity offsetting although how it is measured in money terms, I am not sure. The Environment Bank helps local planning authorities (LPAs) create ecologically diverse landscapes for nature and offer Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) to developers. The Bank agrees a 30 year lease interest on land and the farmers or landowners are paid to develop and manage ‘Habitat Banks’. The scheme is fully funded and risk-free to the landowner. The Bank has a team of ecologists offering support, guidance and monitoring throughout the 30 years. The Habitat Banks in the form of BNG units are sold to developers to provide a mechanism for delivering BNG in all local areas. This makes it easy for both developers and local authorities to comply with the Environment Act and the National Planning Policy Framework. See https://environmentbank.com/

It seems to me that biodiversity offsetting is a much more ethical practice than climate offsetting. Some climate offsetting may be necessary, but the need for housing and industrial development is clear. BNG is a sound way of supporting it without undue harm to the environment.

So, farmers are taking climate and biodiversity change seriously. Not only do they want to deliver benefits to society, they also seek opportunities to make money from the private sector to replace government grants. But before YOU take a plane to Spain, think train!