How a Plant-Based Diet can help the climate

In the first of two articles Martin Coombs, a member of the CA-WN Steering Group sets out his case for following a plant-based diet.

There are many reasons to adopt a plant-based diet (PBD): the avoidance of animal exploitation, a reduction in greenhouse gases (GHG), improvement in the environment and biodiversity, improved food security, and better health. In this article I will concentrate on the effect switching to a PBD would have on the climate, and in a further article will discuss the benefits to the environment and biodiversity of such a change.

I use the term plant-based rather than vegan diet for a good reason. Veganism is not a dietary choice, but the ethical rejection of animal exploitation. To a vegan, any benefits for the climate or health are merely secondary. Although vegans have a plant-based diet, others may adopt a plant-based diet for any of the reasons mentioned above.

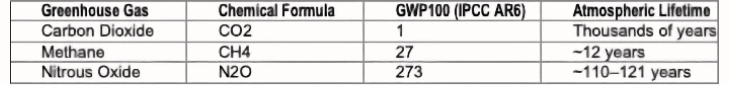

First of all, a refresher on the main greenhouse gases. These are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Global Warming Potential (GWP) measures how much energy the emissions of 1 ton of a specific gas will absorb over a given period, relative to 1 ton of carbon dioxide. The most common timeframe used is a 100-year horizon (GWP100).

By definition CO2 has a GWP100 of 1. It also has an atmospheric lifetime of thousands of years. Non-fossil methane has a GWP100 of 27 but has a short lifetime of about 12 years. Over a 20-year period (GWP20) it is therefore significantly more potent (over 80 times). Nitrous oxide has a GWP100 of 273 and a lifetime of 110 to 121 years, making it the worst of the three main greenhouse gases, and currently the primary driver of ozone layer depletion1. In summary:

The main ways in which animal farming contributes to GHG emissions are as follows2:

Enteric fermentation from ruminants such as cattle and sheep produces methane during the digestive process and is the largest source of livestock emissions. Interestingly, 90% of the methane is from belching.

Manure from livestock produces both methane and nitrous oxide, proportions depending upon how the waste is managed.

Feed production involves the manufacture of nitrogen fertilizers which emit carbon dioxide, and fertilizing crops then releases nitrous oxide. Since 77% to 80% of global soy and a significant portion of maize are grown for animal feed, a shift to plant-based proteins reduces the total area of cropland requiring nitrogen intensive fertilization.

Land use change such as conversion of forest and grassland to pasture and land for growing feed releases stored carbon dioxide from the biomass and soil.

Other energy use such as heating or cooling barns, and the transport, slaughter and processing of livestock further increases the carbon footprint.

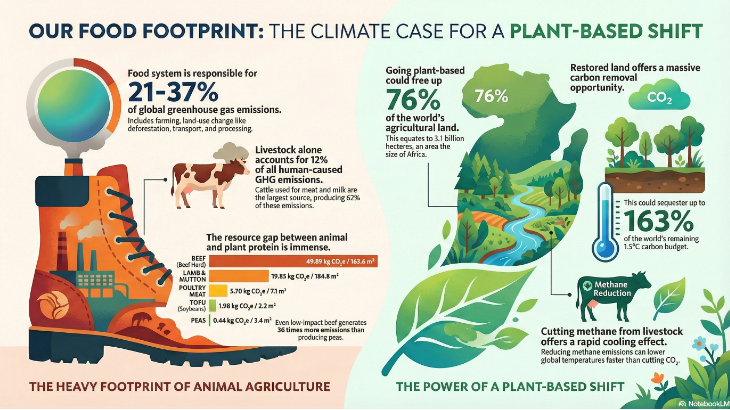

Food production in total accounts for 21% to 37% of global GHG emissions3, and of that animal products and their feed are responsible for nearly 60% of food-related emissions. Estimates of the global carbon footprint of livestock varies from about 12 to 20%. Cattle (beef and dairy) are responsible for 65 to 77% of animal emissions, including accounting for 44% of methane emissions and 53% of nitrous oxide emissions globally4. Importantly, because methane is short-lived, even modest reductions in meat and dairy consumption could lead to a "negative warming" or cooling effect as atmospheric concentrations fall rapidly5.

A transition to a diet that excludes animal products could reduce the global agricultural land requirement by 76% (approximately 3.1 billion hectares, an area the size of Africa)6. This liberated land could then be utilized for reforestation, afforestation, or the restoration of native grasslands and peatlands, all of which serve as massive natural carbon sinks5.

The "Carbon Opportunity Cost" is a metric used to quantify the amount of carbon that could be sequestered if agricultural land were allowed to return to its native vegetation5. Analysis suggests that a global shift to plant-based diets by 2050 could lead to the sequestration of 332 (70% meat reduction) to 547 GtCO2 (full PBD) in living biomass, soil, and litter. For context, this represents 99% to 163% of the total CO2 emissions budget consistent with a 66% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5∘C5.

Meat, milk & eggs provide 37% of protein consumed globally and only 18% of the calories 7. In the UK, livestock and their feed utilise about 85% of the total agricultural land, but only provide 32% of calories and 48% of protein consumed8. On average only about 10% of the calories fed to livestock are converted for human consumption, making it an extremely inefficient use of valuable resources. This inefficiency translates into a massive requirement for cropland and pasture, which in turn drives deforestation and biodiversity loss. The following table shows calorie and protein conversion efficiency for some sectors of animal agriculture9.

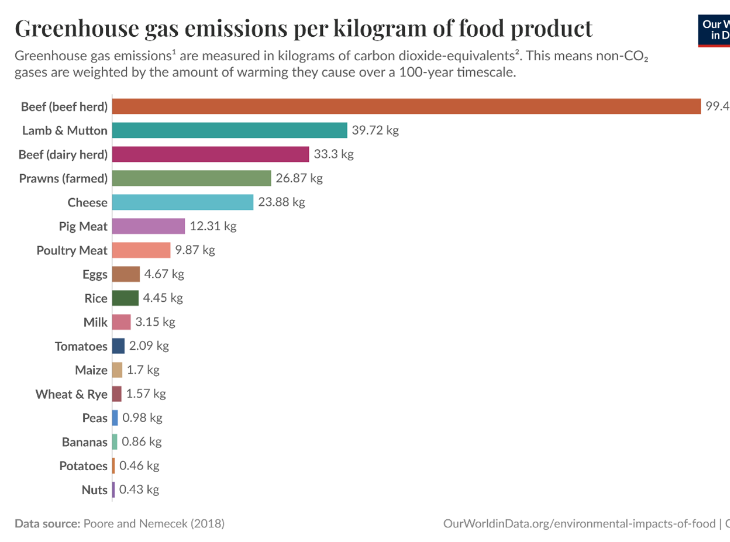

Importantly, which sectors of the food industry have the highest carbon footprint7?

Ruminants (cows, sheep) have the highest carbon footprint, along with farmed prawns and cheese (i.e. concentrated milk). The next highest emitters are pigs and chickens. Rice is an unexpected GHG emitter, owing to the fact that rice production accounts for 10-12% of total global methane, second only to enteric fermentation from ruminants. The carbon footprint of other plant-based foods is minimal in comparison to emissions from meat, dairy and eggs.

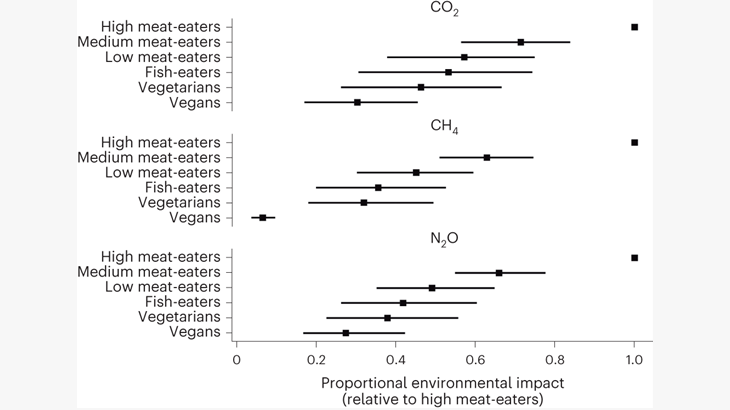

In the comparison below GHG emissions for vegans, vegetarians, fish-eaters, low meat-eaters (<50g/day) and medium meat-eaters (50-99g/day) were compared to high meat-eaters (>100g/day). A PBD resulted in 70% lower CO2 emissions, 93.5% lower CH4 emissions, and 73% lower N2O emissions compared to high meat-eaters. Even moving from being a high meat-eater to a low meat-eater resulted in more than a 30% reduction in GHG emissions10.

What actions can you take, therefore, to reduce your food carbon footprint? I would suggest the following:

1. Stop or reduce eating meat. In particular avoid meat from the heavy GHG emitters (cows and sheep).

2. Stop or reduce cheese consumption. About 10 litres of milk are required to make a kilogram of cheese, hence its high carbon footprint. Limit cheese to special occasions or use soft cheeses, which have a lower global warming potential.

3. Stop or reduce fish consumption.

4. Limit rice consumption, because of its high methane emissions.

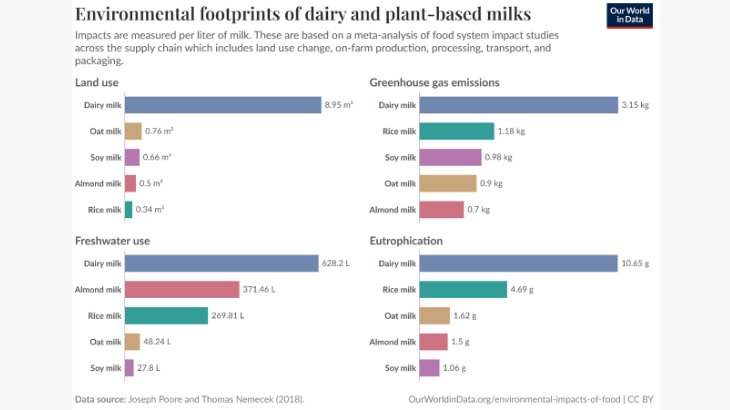

5. Switch from cow’s milk to a plant-based alternative. The following table might be useful in making your decision7. [N.B. Eutrophication is the process where excessive nutrient runoff—primarily from fertilizers and animal waste—triggers explosive algal growth that depletes oxygen in water bodies, often leading to "dead zones" and the release of potent greenhouse gases].

6. Switch to a fully plant-based diet, with the added benefits of reducing animal exploitation, improving the environment and biodiversity, and better health.

7. Avoid wasting food. Food waste accounts for 6-10% of global GHG emissions.

In my next article I will look at the benefits that a plant-based diet can confer on the environment and biodiversity.

References

1. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 184 pp., doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

2. Blaustein-Rejto, D and Gambino, C (2023) Livestock Don’t Contribute 14.5% of Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions, The Breakthrough Institute

3. Feeding 10 billion people by 2050 within planetary limits may be achievable, say researchers - Oxford Martin School, https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/news/201810-springmann-nature

4. FAIRR (2025) Greenhouse Gases From Intensive Animal Agriculture https://www.fairr.org/resources/knowledge-hub/greenhouse-gases

5. The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344194763_The_carbon_opportunity_cost_of_animal-sourced_food_production_on_land

6. Why Environmental Impact Should Influence Your Diet | Earth.Org, https://earth.org/data_visualization/why-environmental-impact-should-influence-your-diet

7. Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992

8. Ruiter, H., J. Macdiarmid, R. Matthews, T. Kastner, L. Lynd and Smith, P. (2017) ‘Total global agricultural land footprint associated with UK food supply 1986–2011.’ Global Environment Change, 43, 72-81

9. Meat conversion efficiencies - Alexander et al. (2016) – processed by Our World in Data. “Energy conversion efficiency (Alexander et al. (2016))” [dataset]. Meat conversion efficiencies - Alexander et al. (2016) [original data]

10. Scarborough, P., Clark, M., Cobiac, L. et al. Vegans, vegetarians, fish-eaters and meat-eaters in the UK show discrepant environmental impacts. Nat Food 4, 565–574 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00795-w